Ebonic Embrace: Celebrating Black Love Vernacular Through Art

While African American Vernacular English is the new proper name of what was previously referred to as Ebonics, there is something romantic in the term ebonic to refers to language as being swarthy. That word has such visual connotations in particular before political correctness. Artwork, similarly, captivates our brand of love and care unique to our visual vernacular.

Care is defined in The Care Manifesto: The Politics of Interdependence as “a social capacity and activity involving the nurturing of all that is necessary for the welfare and flourishing of life.” Since various types of relationships, acts, words, intimacies, private mundane practices, spiritualism, and “always-presentness” are encompassed in the term, it is important to document the story of Black love and care throughout history. Documenting it proves its existence and vitality in the community, countering many demeaning stereotypes and narratives by white supremacist capitalist patriarchy. Also, the art world monetizes the depiction of Black pain (Open Casket by Dana Schutz, as an example depicted outside of our community, and with truth-telling within our communities since our voices are so stifled). However, the narrative of love, care, and tenderness are equally as important

Care is defined in The Care Manifesto: The Politics of Interdependence as “a social capacity and activity involving the nurturing of all that is necessary for the welfare and flourishing of life.” Since various types of relationships, acts, words, intimacies, private mundane practices, spiritualism, and “always-presentness” are encompassed in the term, it is important to document the story of Black love and care throughout history. Documenting it proves its existence and vitality in the community, countering many demeaning stereotypes and narratives by white supremacist capitalist patriarchy. Also, the art world monetizes the depiction of Black pain (Open Casket by Dana Schutz, as an example depicted outside of our community, and with truth-telling within our communities since our voices are so stifled). However, the narrative of love, care, and tenderness are equally as important

The seated primordial couple by the Dogon people in Mali comes to mind as one of the first images of Black love, companionship, and childrearing. It showcases a social unit founded on connectivity, protection, and abundance. While kinship and romantic relationships transcend the nuclear family structure today, Black love iconography in all of its forms, nuances, and complexities matters. Contemporary artists depict how loving is an art and visual works of the diaspora are a certain type of memory keeping and an expression of love. Furthermore, tenderness increases in value when surveillance, lack of privacy, and oppressive structures are realities of the Black experience in America. But to push back against those structures is a type of ritual and divine expression: “Intimacy reveals something deeply human in us. We need each other on a practical level…it’s analogous to what I understand prayer requires…it’s at once akin to and the same as devotion.”

Psalms II: Voodoo Like You Do by Steve Prince

Prince, who grew up in New Orleans, displays a couple in a monochromatic celestial scene. Depicted in a vernacular style, a femme and masc figure intertwine through a gesture. Instead of a skeleton peeking through their silhouetted bodies, a display of voodoo vévé-like symbols decorates their bodies. vévé comes from a long tradition of summoning the Iwa through a transference point. Often these cosmograms are made up of cornmeal, ashes, or palm oil depicting a certain deity and a conduit to their powers on the earth side. Also, Prince depicts adinkra, an ancient script of the Akan Empire in Ghana, a slave ship diagram, a Taoist yin-yang symbol, and the Christian ichthys symbol. Transcribing body gestures with these intricate patterns demonstrates how love is the culmination of ancestors before you, a hybrid spiritual experience, and the title suggests the sentiments of the 1997 film Love Jones — that love is a predetermined uncontrollable force, a magnetism, and an enigma.

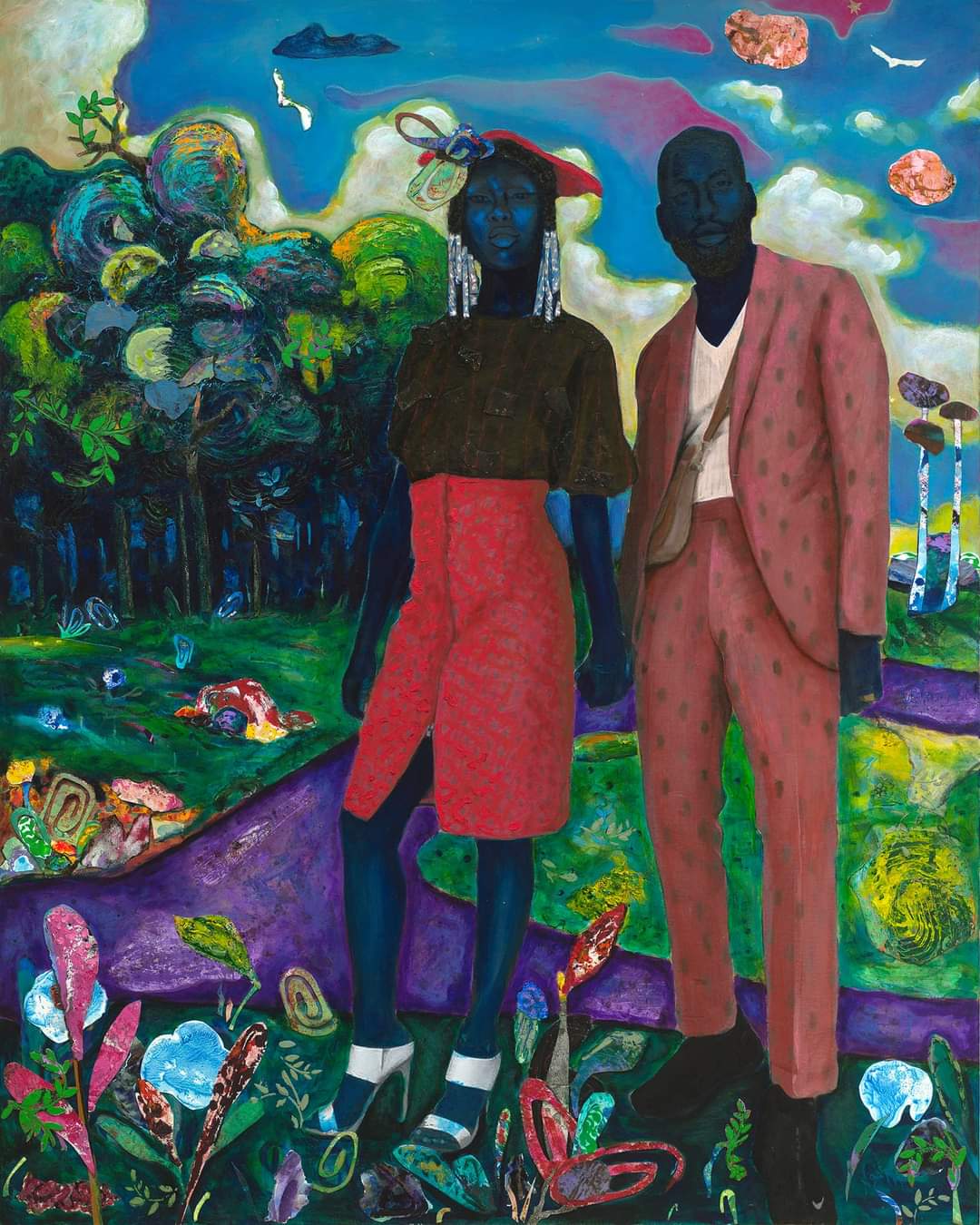

Return to Eden #1 by Najee Dorsey

A lush, dream-like background depicts an idyllic scene of a couple in a thriving environment. This depiction is in stark contrast to some of the Poor People’s Campaign series where he depicts the detritus of environmental racism intermingled with childhood innocence and whimsy. D. Amari Jackson speaks to these tonal changes when he says, “One can’t help but notice the remarkable transformation, from stark and bare to pregnant with beauty; from agitation and conflict to serenity and resolution; from ongoing loss to eternal triumph; from the hellish hues of an environmental nightmare to the vibrant and playful pastures of Eden.” What does this depiction contribute to the language of Black Love? It demonstrates how love imagines beyond the current circumstances and envisions flourishing in places of lack. This depicts joint love for all of creation and acknowledges our interdependencies.

All About Love by Lavett Ballard

Reclaimed fences, meant to distinguish private property borders, transform into a type of ‘shrine’ in Ballard’s work: she collages figural archival imagery, flowers, butterflies, gold leaf decoration, and circular motifs in her work awakening the divine feminine. She says, “To embody the struggle specific to African Americans I often layer, tear, and burn to show tension in what is a collection of photos often seen and unseen by the public, and as a personal offering, I include personal family photos from different periods in a way to not only honor the ancestors of others but my own.” All About Love, evoking the book by bell hooks of the same title, displays a double-vision of a couple. They appear larger in the foreground and smaller in another pose in the background. Additionally, the photographs are monochromatic except for the redness of the femme figure’s lips. The warpedness of the fences that Ballard plays with, and the singed parts of the work demonstrate the beauty in imperfection and all a part of the story of loving.

Keep Me Safe by Archie Mason

The Underground Railroad Series, a landscape painting of Underground Railroad Historic Sites, Mason describes this work as, “Part of my Quilt Code Series, it consists of painting, graphite drawings, etchings, and serigraphs.” There are two figures: a woman and a child embracing, wrapped in a narrative-based quilt with patterns that have various meanings. As many enslaved people communicated through quilts and cornrows escape routes were whispered through various types of patterning. The blue symbol is the North Star, our symbol of salvation, guidance, and wisdom. Because of how large the embrace is by taking up the bottom half of the print with the top of the woman’s head as the precipice, it shows her as mountain-like and the matriarchal head. As the work’s title suggests, safety is a huge part of loving within the Black community as within safety, there’s a sense of privacy and only an in-crowd knowing and holding onto secrets. Sharing these secrets is a crucial part of loving and rearing the next generation of culture-bearers.

Keeping the Culture by Kerry James Marshall

The viewer peers into a familial private scene in a mid-century modern living room. The children are captivated by a seemingly anachronistic projection technology called a hologram with Africa’s axis at the center while the presumed parents have a ‘fresh’ moment in the corner. According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, “The family is living in the future in a home beyond Earth’s orbit, as evident by the view of the solar system outside their windows.” While that subject matter may be a commonplace home scenario, the combination of the technology, large windows displaying a galaxy and a shooting star, and Afrocentric decor creates an Afrofuturist nuclear family scene.

Some of the decor includes a Chiwara mask with its signature antelope-like shape in the background. Chiwaras are from the Bamana people of Mali. It is a symbol of agricultural fertility. The femme figure in the corner holds onto a Kanaga Mask from the Dogon people of Mali. Kanaga Masks are known for their double-barred superstructure which is worn while teenagers dance to demonstrate their strength and its amorphic crocodile imagery represents ushering people from the realm of the living to the spiritual world. Christie’s notes how this depiction transcends the life experience that Marshall had living through the Civil Rights Movement and envisioning a greater transcending future. They write, “Ushering in a new stage of the artist's output, Keeping the Culture shifts focus from the failed utopia of urban renewal and the commemoration of Civil Rights Era heroes in favor of a more technically refined meditation on the preservation of the traditional and spiritual values that shaped a culture.” The title Keeping the Culture showcases how families impart knowledge, aesthetics, and cultural norms. This social unit is a way that both love for culture is expressed among love for each other through the passing down of stories and traditions.

Loves Ambiance: Hues of Humanity Series by Dontanarious Kelly

Similar to Najee Dorsey’s Return to Eden #1, Kelly depicts a color-field-based Edenic environment engulfing and embracing a seated couple on a couch. There is both serenity and joy in their faces. This reinterpretation of a familiar domestic scene offers a further interpretation and imagination of what the daily act of talking on a couch cultivates. Even the crossing of their arms and the tilting of their heads towards each other makes a heart shape. The hummingbirds buzzing around the couple evoke how birds in African lore represent mystery, life, perfection, and rebirth. These concepts and the fading of the edges of the painting narrativize these private moments where couples steal away a frozen moment in time opening a portal to the sublime.

Overall, there are infinite ways of loving as shades of melanin and they all are equally beautiful. Black love and care are important to counter stereotypical, harmful narratives, showing community vitality and resistance. Love is our legacy, our ingredient to a flourishing future, and a way that cultural preservation occurs in fictive kinship, families, and other social units of connection.

Consider a purchase of yard art couples, ranging from $45-$89, all about love for the culture!